Why should our constitutional protections be interpreted as they were understood when written, without taking account of any of the values that have evolved in contemporary society, as originalists insist? Unable to answer that difficult normative question directly, originalists have defended their approach with the claim that it constrains judges more than other methods of interpretation. Does it?

If the Constitution is limited to the original meaning, the theory goes, the space for judges to make up meanings is curtailed. And in a world where a significant concern is that judges are not umpires calling balls and strikes, but political animals seeking to cater to the interests of their political allies, constraint has social value.

On its face, the claim has some theoretical plausibility – if original meaning could be credibly mined, tested and articulated, it could limit the discretion of judges and provide some determinacy to the law. On the other hand, the tool is only as good as those who are using it. If the historical record is fuzzy, if the judges in question lack skill at doing nuanced historical analysis and, worse, if they are motivated to select the history that yields meanings they want, then originalism won’t constrain much. The question, as we see it, is empirical.

In a duo of cases in 2008 and 2022, in the politically charged area of gun law, the Supreme Court presented us with an opportunity to test the “originalism constrains judges” claim. First, in 2008, in Heller, the Court recognized a new individual right to bear arms. Importantly for our empirical analysis, when lower courts were asked to enforce the new right to gun ownership in cases challenging gun restrictions, they coalesced around using the same non-originalist analysis that they use for other constitutional rights. Under this standard balancing approach, when a gun regulation is challenged, judges ask whether the government has demonstrated an important public interest, such as public safety, sufficient to justify the restriction and whether the regulation furthers that interest without unnecessarily burdening the constitutional right. Then, in 2022, in Bruen, the Court announced that it was displeased with what the lower courts had been doing with the Heller right to guns, as the test they were using gave too much credence to claimed government interests. Instead, the Court decreed, courts from now on would ask a purely historical question: whether the government regulation being challenged had any kind of analogue in the founding era. Balancing was out and originalist historical analysis was in.

That abrupt change allowed us to compare lower court decisions in the period between 2008 and 2022 (the balancing-test era) against those from the 2022 to 2024 era (the original-historical-analysis period). And we can look to see whether the results appear determinate across the board or driven by personal value preference, based on certain predictions about the likely personal proclivities of judges (e.g., White Republican men tend to be pro gun; Democratic women tend to be less favorable toward guns).

Using a dataset of all lower federal court opinions addressing a Second Amendment claims from 2000 through 2023, we counted all judges’ votes cast as either favorable or unfavorable to the gun-rights claim. We then merged information on the judges’ personal characteristics that have been shown to be related to support for gun rights, such as party, gender and race. The goal: To see whether the more originalist, history-based test of Bruen led to more favorable decisions for gun claims, regardless of the judges’ personal views, or whether it invited individual judges to decide based on personal preferences.

Turns out, the Bruen test seems to have enabled those judges already disposed to support gun rights (Republican and male judges) to increase the favorable outcomes for gun claims, while those not as enthusiastic about the Second Amendment (women and Democratic judges) used the same test but did not increase their rate of support for gun claims. Whoops.

Looking further, we found that the younger Republican judges (in the age range where they might be competing for promotion to a higher court) showed the greatest increase in gun support. In other words, personal proclivities were likely at play again. Whoops again. Originalism does not seem to be constraining. If anything, maybe the opposite.

Caveats are in order, of course. Maybe gun law is different? More data, across more subject areas where the Court has ordered historical originalist analysis to replace balancing, would help. And maybe the difference in analysis between younger Trump judges and older judges is not a difference in personal proclivities, but a different genuine understanding of the law considering that the older judges, having been schooled in the old law and analysis, might find it hard to do the new type of analysis. Or maybe, the environment today is too politically charged for originalism to do its work dispassionately – and perhaps it will do a better job once partisan polarization calms down. Again, more data can help.

Bottom line though, from what we have so far, is that the data do not show that originalism constrains judges. To the contrary, judges’ discretion seems to have increased under originalism. As of now, from the data we have examined, the claim that originalism constrains strikes us as fanciful. And that returns the focus back to asking why originalism is a good idea.

Article Details

The Constraining Effect of “History and Tradition”: A Test

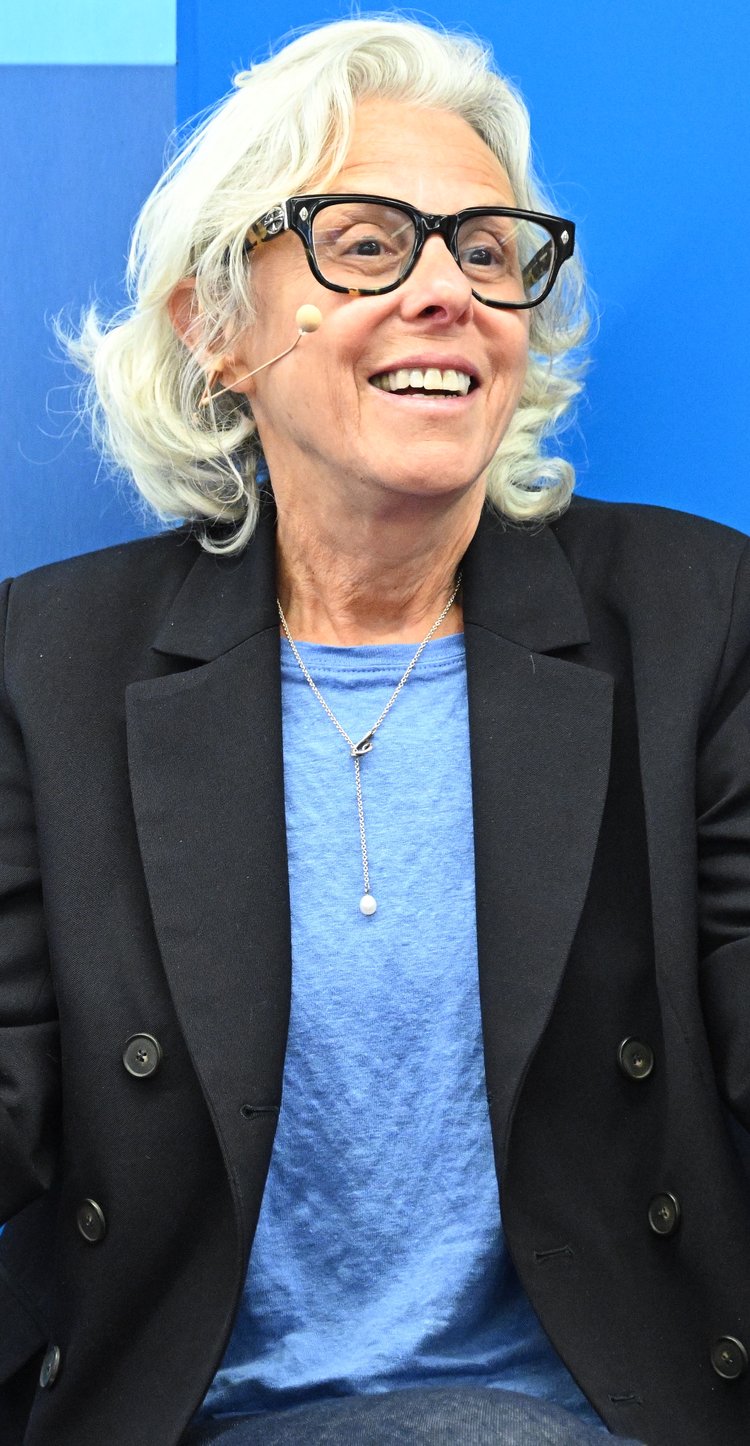

Rebecca L. Brown, Lee Epstein, Mitu Gulati

First published: June 13, 2025

DOI: 10.1177/00027162251335725

The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science